Preventing violence requires fixing social power imbalances at the deepest level – the level the Racial Equity Institute and NCCADV call the Groundwater level. The ‘groundwater’ can be understood as the overarching culture and structure of our society.

Power inequities in the groundwater determine the social context of people’ everyday lives through institutions and systems - such as education, health care, the built environment, community context, and employment. In the field of public health, these are called the social determinants of health.

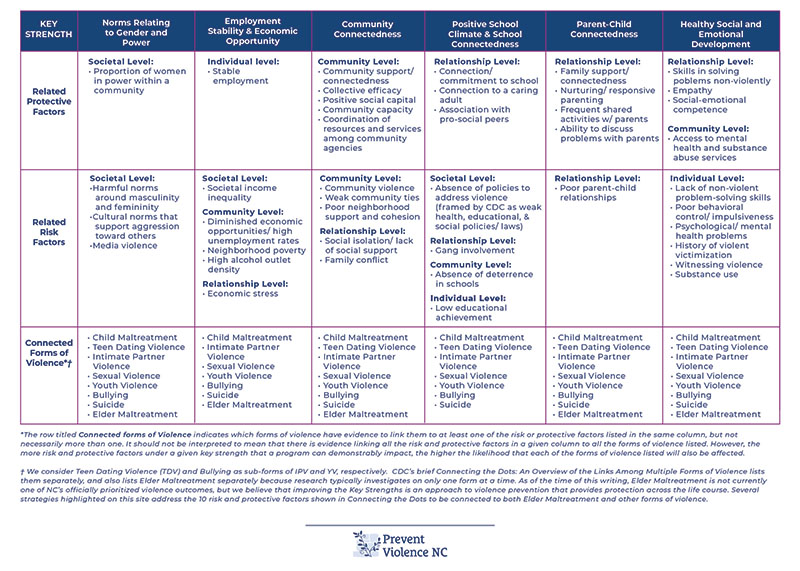

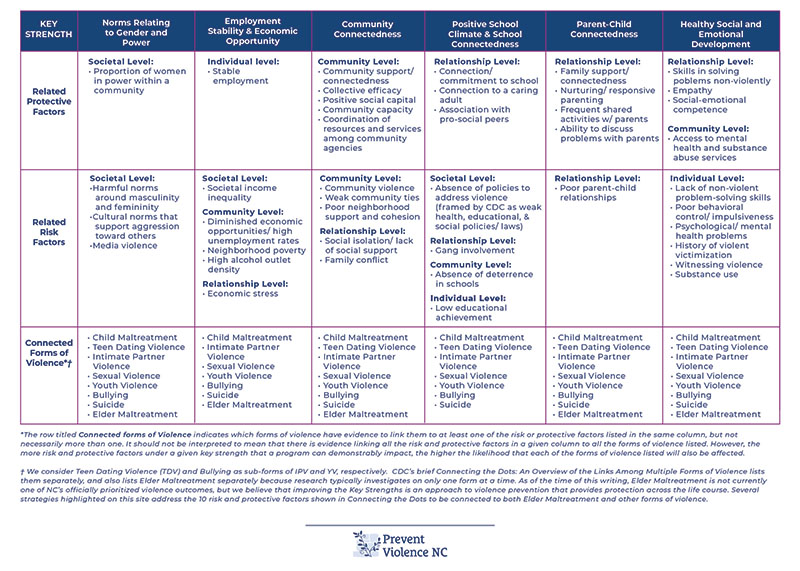

These systems and institutions influence people in specific ways that can protect against violence perpetration (protective factors) or put people at risk for doing harm (risk factors). We’ve grouped these risk and protective factors into six related clusters that we call Key Strengths.

We believe that communities working to improve the Key Strengths in a coordinated way across all the social determinants of health and levels of the social ecology can function to “clean up the groundwater.” In other words, working together across systems to shift power inequities in our structures and culture can begin to address violence where it begins.

And bolstering the Key Strengths is how.

And bolstering the Key Strengths is how.

Each Key Strength is a cluster of related risk and protective factors that are important for preventing all five of NC’s prioritized violence: Child maltreatment, domestic violence, sexual violence, suicide, and youth violence.

Strategies to bolster any of the Key Strengths can be implemented across all levels of the social ecology, but they do have different ‘home’ levels of influence. For example, Healthy Social and Emotional Development is a cluster of risk and protective factors that occur at the individual and interpersonal level, but there are strategies to strengthen them that can be implemented in communities and through social policy.

One example of a societal level intervention that strengthens the individual-level risk and protective factors is the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. This law generally prevents health insurance plans offering mental health or substance use disorder benefits from restricting coverage for those benefits in comparison to their coverage of medical and surgical health services. Meaning, if a plan offers mental health coverage it should be comparable to coverage for medical care. The Affordable Care Act strengthened this requirement by including mental health and substance use disorder care in the ACA’s list of 10 Essential Health Benefits that most health plans must offer. Thus, access to mental health services and treatment for substance use disorders significantly increased in communities all across the country – a national level intervention improved several risk and protective factors that fall at the individual level under the key strength, Healthy Social and Emotional Development.

In the descriptions below, the 'home' sphere of influence is listed under the name of each Key Strength - but on the Strategies and Resources sections of the website you can learn more about strategies to implement at across the social ecology (click on image to see larger view).

Download this table as a PDF file.

Definitions of the five violence outcomes prioritized for prevention in NC

Child maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes harm to a child in the form of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse or neglect by a parent, caregiver, or authorized custodian such as a coach, teacher, or clergy person. Abused children often suffer physical injuries. In addition, maltreatment causes stress that can disrupt early brain development, which may continue to have an impact into adulthood.

Prevent Child Abuse NC reviews state reported statistics on child abuse and neglect in North Carolina and provides current summaries here.

Intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV), or domestic violence as it’s often called, is a pattern of domination in which perpetrators intentionally choose to cause fear, injury, and/or pain to maintain power and control over their current or former intimate partners. IPV can occur between married, unmarried, divorced or separated partners, and among teens or adults. In addition to physical violence, abuse can be sexual, emotional, financial, and can include stalking. One in four women, and one in ten men have experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime, according to the 2015 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey.

North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence tracks IPV-related homicides in NC every year.

Suicide

Suicide is death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior. Specific groups in the population, such as youth and young adults, older adults, and military veterans are more vulnerable to suicide and self-inflicted injury. In addition to death and serious injury, suicidal behavior often produces a heavy burden of medical expenses, disability, loss of wages and productivity, and feelings of guilt, anger, and depression in victims and family members.

Though rarely discussed, suicides outnumber homicides two-to-one, resulting in nearly 1,300 suicides in North Carolina each year . Deaths represent only a fraction of the outcome of suicidal behavior; non-fatal self-inflicted injuries from suicide attempts requiring hospitalization or an emergency department visit are much more common than fatal self-inflicted injuries.

Youth violence

Youth violence includes various behaviors, such as fighting, bullying, gang-related violence, and homicide. These behaviors involve the intentional use of physical force or power by a young person between the ages of 10 and 24 to threaten or harm other people. Young people can be involved with violence as victims, perpetrators, or witnesses.

In North Carolina, the Department of Public Instruction aggregates data collected every two years at the county level on the prevalence of youth violence using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Societal

Societal Community

Community

Gender is a set of social and cultural roles that are typically assigned at birth based on an infant’s external sex characteristics, such as genitalia.

Gender roles vary across cultures, and the two most common genders are woman/female and man/male, although there are many more possibilities some of which are unique to specific cultures. For example, Muxe people are a unique and valued part of the Zapotec community in Oaxaca, México.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research note that gender “influences how people perceive themselves and each other, how they act and interact, and the distribution of power and resources in society. Gender is usually conceptualized as a binary (girl/woman and boy/man), yet there is considerable diversity in how individuals and groups understand, experience, and express it.” This Map of Gender Diverse Cultures has more information about the history of gender diversity around the globe.

The culturally-specific rules and expectations for behavior and self-expression associated with these social roles known as gender norms. Sometimes norms are explicit and formal – often, these are clearly taught by authority figures as “what people should do.” But there is another type of social norm that is subtle, informal – yet very influential, which can be understood as “the way the world is.” Both are important to address when implementing strategies under this Key Strength.

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Gender norms create expectations of specific behaviors that vary for men and women. For example, being male is traditionally associated with tough or aggressive behaviors. Harmful norms around masculinity and femininity can hamper healthy social and emotional development in unique ways for different genders, and are risk factors for all five types of violence North Carolina has prioritized for prevention

Differences in gender norms create expectations for how power will be distributed in families and communities, often in ways that assign advantage to masculinity over femininity. This can contribute to an increased risk of violence perpetration in many forms by, and also toward, men.

Conversely, the status of women and their power within a community can act as a protective factor against violence perpetration. A study by Whitaker (2014) found that “for each unit increase in the proportion of women in powerful positions within a county, there was a 71% decrease in the risk that control-seeking [men] would perpetrate physical IPV … The findings support the optimistic argument that as women gain more formal power in a community, control-seeking males are less likely to perpetrate physical IPV.” Based on this finding, it is reasonable to support the broad strategy of promoting women’s formal power (i.e. increasing the visibility of women lawmakers, civic leaders, business owners, etc.) in a community as a means to prevent and protect against IPV, as well as other forms of violence. Signs that women are achieving more formal power may include political representation, wages, economic opportunity, and access to resources.

Norms and the status/power of women within a community have a mutually reinforcing relationship. The more power women have in a community, the less likely harmful gender norms will exist. Similarly, harmful gender norms often prevent women from gaining power within their communities.

Promoting gender equity across the social ecology is an integral component of holistic violence prevention efforts. It is important to note, however, that despite the wide-spread use of interventions to address gender norms, few have been rigorously evaluated. Additionally, existing programs are often limited by their focus on norms within the traditional gender binary of woman/man, leaving out and thus further marginalizing people of other genders.

Strategies to address harmful gender norms include educational workshops in schools or community settings, media campaigns, and the intentional incorporation of gender analysis into programs, laws, and policies. Interventions that combine several of these strategies are more effective than each one is alone. Because gender norms and the status of margenderalized people are reciprocal, strategies to foster gender equity require an approach that simultaneously works to shift norms and support the equitable distribution of power for marginalized groups.

For more resources on Norms Related to Gender and Power, visit our Resources section.

Economic Stability and Opportunity

Levels of the Social Ecology:

Societal

Societal Community

Community

Economic Stability and Opportunity can be understood as having enough material resources to provide for your, and your family’s basic needs, and ample, viable opportunities to improve your economic status.

In terms of employment, it is having a steady job that pays a living wage or better, and ample opportunity in your neighborhood for everyone who needs such a job to obtain one.

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Limited community economic opportunities and a high unemployment rate are risk factors for all five forms of violence prioritized for prevention in NC.

Diminished economic opportunity and high unemployment not only reduce the potential for individual stable employment - but are also linked to greater community disorganization, and lower social cohesion and trust. Research has shown that communities that have been systematically dis-invested from economic resources and opportunities have higher rates of violence.

Researchers at Duke University found links between community economic downturns, youth educational achievement, and youth suicidal ideation and attempts. Stable employment at the individual level may also play an important role in reducing the economic-related family and relationship stress believed to influence some forms of violence against children and intimate partners.

Strategies to increase economic stability and opportunities vary widely. One of the largest programs to increase employment stability and opportunity in U.S. was the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The New Deal federal program lasted from 1935 – 1943 and employed approximately 8.5 million people in the arts, construction, and civic improvement projects. Research suggests that lowering the early retirement eligibility for another New Deal program - Social Security - lowered suicide rates among men over age 62. More recent initiatives range from sector-specific job training and literacy programs, to tax policy to encourage job growth, and policies to enhance access to job-protected paid family leave.

At every step in the process of developing and implementing a strategy to increase employment stability and economic opportunity it is critical to assess how the program might inadvertently reinforce existing racial inequities and health disparities. Because of the entrenched historical inequities and cultural biases in the groundwater, programs that appear neutral have the potential to widen - rather than close - the gaps they seek to address.

For more resources on Economic Stability and Opportunity, visit our Resources section.

Community Connectedness

Levels of the Social Ecology:

Community

Community

Community Connectedness describes the strength and quality of social ties between members of a community and is a protective factor for all five forms of violence prioritized for prevention in NC.

One key component of Community Connectedness is collective efficacy.

Collective efficacy is a two-part concept that can be described as a willingness to intervene on behalf of the common good, plus a group-level “I think I can” – or rather, “we think we can.”

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Higher levels of collective efficacy are associated with lower rates of youth violence, child maltreatment, and intimate partner violence. Social capital is a related concept that describes the relative social influence and power possessed by individuals and groups. Inequities in social capital have been linked to intimate partner violence and child maltreatment, chronic disease, infectious disease, income inequality, as well as a host of other health concerns.

Initiatives to increase Community Connectedness and related concepts like collective efficacy and social capital can take many forms. They include tree-planting and urban greening initiatives, civic engagement activities, community gardens, community art and social centers, community-based after-school programs, and community health worker programs. In general, they seek to foster trust and solidarity among members, and engage people in an activity that promotes community well-being.

An important historical program that continues to influence levels of Community Connectedness today is a neighborhood-level initiative implemented across the U.S. by the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation. The HOLC identified specific neighborhoods and green-lined them throughout the mid-1900s, promising banks they would insure home mortgages in these areas. Green-lining encouraged banks and developers to invest in particular neighborhoods, and to avoid investing in others (those that were yellow- or red-lined). This in turn, created a pattern of in which some neighborhoods possessed built environments that included parks and other amenities which encourage community-connectedness, while others do not. Today, the green-lined neighborhoods have lower levels of concentrated poverty, and higher levels of Community Connectedness than the yellow- and red-lined communities.

For more resources on Community Connectedness, visit our Resources section.

Positive School Climate and Connectedness

Levels of the Social Ecology:

Community

Community Interpersonal

Interpersonal

School climate is the “quality and character of school life.” It is the sum of the values, norms, expectations, and spaces that shape the social and physical environment of a school, making it a place that may feel safe and welcoming or hostile and intimidating.

School connectedness exists when children feel engaged with their school and cared for by school personnel. School climate and connectedness can be mutually reinforcing.

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Together, the quality of school climate and connectedness can influence rates of sexual violence, youth violence, bullying, suicide, and, in some cases, teen dating violence. They are also tied to academic achievement, school attendance, and health risk behaviors such as alcohol, drug use, and early sexual initiation.

There are important differences to note in school connectedness experienced by students of different racial and gender identities. Research has shown that differences in connectedness by race stem from the ways school culture and climate have been shaped by practices that purposefully segregated students by race. In North Carolina, resistance to the racial integration of public schools was so strong, that it wasn’t until seventeen years after Brown vs Board of Education that school systems across the state began to desegregate in earnest by bussing students into different neighborhoods. The catalyst for compliance in 1971 was the Supreme Court upholding a ruling that required Charlotte schools to finally desegregate.

Today we see these differences in connectedness show up in the stark racial disparities in rates of discretionary disciplinary consequences imposed by school administrators. Discretionary is the term applied to disciplinary consequences that school officials have decision-making authority about whether to impose – or not – which includes discretion over the nature of the punishment. Mandatory discipline is imposed by state law for specific behaviors, and local school or district level officials are required to impose the legislated consequences.

A longitudinal study done in Texas, called Breaking Schools’ Rules, examined the school and juvenile justice records of nearly 1 million students, a full census of every middle school student in the state from 2000 - 2002. Because the dataset included six years of educational and juvenile justice records for these one millions students, researchers were able to control for 83 different variables and thus isolate the effect of race on student disciplinary outcomes.

They found that rates of removal from school for serious offenses, those known as “mandatory violations” (such as sexual assault or bringing a weapon to school) were similar for white, Hispanic and Black students. But when school officials had discretion over whether or not to impose a suspension or expulsion, “African-American students had a 31% higher likelihood of experiencing a discretionary action, compared to otherwise identical white and Hispanic students.”

Gender also has a significant impact on student experiences of school climate. Student advocates, parents, and education experts point out that dress codes often comprise a list of violations heavily weighted toward styles and types of garments worn by girls. The justification for including these in the dress code is often that the items are distracting, sending students the message that boys’ ability to pay attention in school is the responsibility of the girls in their class. LGBTQ students are made more vulnerable to bullying related to their gender expression by these rules, to the point that 54 – 64% of LGBTQ students experience bullying based on their gender or gender expression. Gendered codes are consistently also racialized dress codes. Locs, hair wraps, and other ways of wearing natural Black hair are frequently disallowed, and enforcement of the codes follows the same racially discriminatory patterns described in the Breaking Schools’ Rules study.

Strategies and policies to improve school climate and connectedness work best when designed to address the lingering effects of the inequitable design of the U.S. education system. Most programs usually take place in the school, but can involve the community more broadly, as is the approach of organizations like Communities in Schools. High quality school-based individual and relationship level approaches abound and the Resources section has links to numerous evidence-based/informed options, but it is important to keep in mind that these approaches are most effective when done in conjunction with structural changes that address inequity.

For more resources on School Climate and Connectedness, visit our Resources section.

Parent-Child Connectedness

Levels of the Social Ecology:

Interpersonal

Interpersonal Individual

Individual

According to researchers with ETR Associates, Parent-Child Connectedness “is characterized by the quality of the emotional bond between parent and child and by the degree to which this bond is both mutual and sustained over time."

When Parent-Child Connectedness is high in a family, the “emotional climate is one of affection, warmth, satisfaction, trust, and […] cohesion.” Although most of the available research deals with connections between parent and child, it is likely that the findings hold true for non-parental primary caregivers, such as grandparents who are raising their grandchildren.

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Parent-Child Connectedness has been linked in the research literature to over two dozen adolescent health and wellbeing outcomes, leading some to consider it a super powerful protective factor worthy of significant focus. The absence of Parent-Child Connectedness is a risk factor for all five of NC’s prioritized violence outcomes, in addition to bullying and teen dating violence.

Most initiatives to support Parent-Child Connectedness are education or counseling programs working with parents and children at the interpersonal or individual levels. However, some strategies work more broadly to facilitate stronger parent-child positive bonds, such as policies that increase the amount of time working parents have available to spend with their children.

For more resources on Parent-Child Connectedness, visit our Resources section.

Healthy Social and Emotional Development

Levels of the Social Ecology:

Interpersonal

Interpersonal Individual

Individual

The foundations of social, emotional, and behavioral health form in early infancy, and grow throughout adolescence. The Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, and Families describes social-emotional competence as “the developing capacity to experience and regulate emotions, form secure relationships, and explore and learn—all in the context of a child's family, community and cultural background.”

As children age, social emotional competence evolves to include self-confidence, motivation, and impulse control. Empathy, or the ability to identify and share the emotions of another person, also emerges in infancy. Empathy is affected by parental warmth, attachment, and emotional guidance. In addition to being crucial elements of violence prevention, these factors are essential to school readiness and healthy relationships.

Why it’s important for violence prevention:

Healthy social and emotional development builds skills known as social emotional competence, impulse control, empathy, and non-violent problem-solving. These are important individual-level factors that protect against a person’s likelihood of perpetrating many forms of violence, and in the case of child maltreatment, they may also protect against victimization.

Strategies to support healthy social and emotional development take many forms. Most are programs conducted with parents, other caregivers, or in schools.

For more resources on Healthy Social and Emotional Development, visit our Resources section.

And bolstering the Key Strengths is how.

And bolstering the Key Strengths is how.![]() Societal

Societal![]() Community

Community

![]() Societal

Societal![]() Community

Community

![]() Community

Community

![]() Community

Community![]() Interpersonal

Interpersonal

![]() Interpersonal

Interpersonal![]() Individual

Individual

![]() Interpersonal

Interpersonal![]() Individual

Individual